Some may see the use of the irregular verb “be” in the above title as aspirational, on becoming something they are not, such as a metallurgist or botanist or racecar driver.

It may seem odd that anyone has to become something that so many millions of people already seem to be. Being a record collector has been almost a natural element of growing up for anyone with some music appreciation and a bit of disposable income. For over a hundred years, the myriad of music genres and capitalist marketing have made it incredibly easy to accumulate music of any type in multiple formats, from cylinders to vinyl records to CDs to digital bits.

But if we look at what it takes to be a serious record collector these days, we’d understand that it’s not so easy to simply buy a lot of records (of whatever format) of the music we like and call ourself a record collector. This is a field that has grown much too sophisticated to call any accumulation of material a “collection.” One may have a hundred records, or thousands, and still not be a record collector.

The Boomer Collector

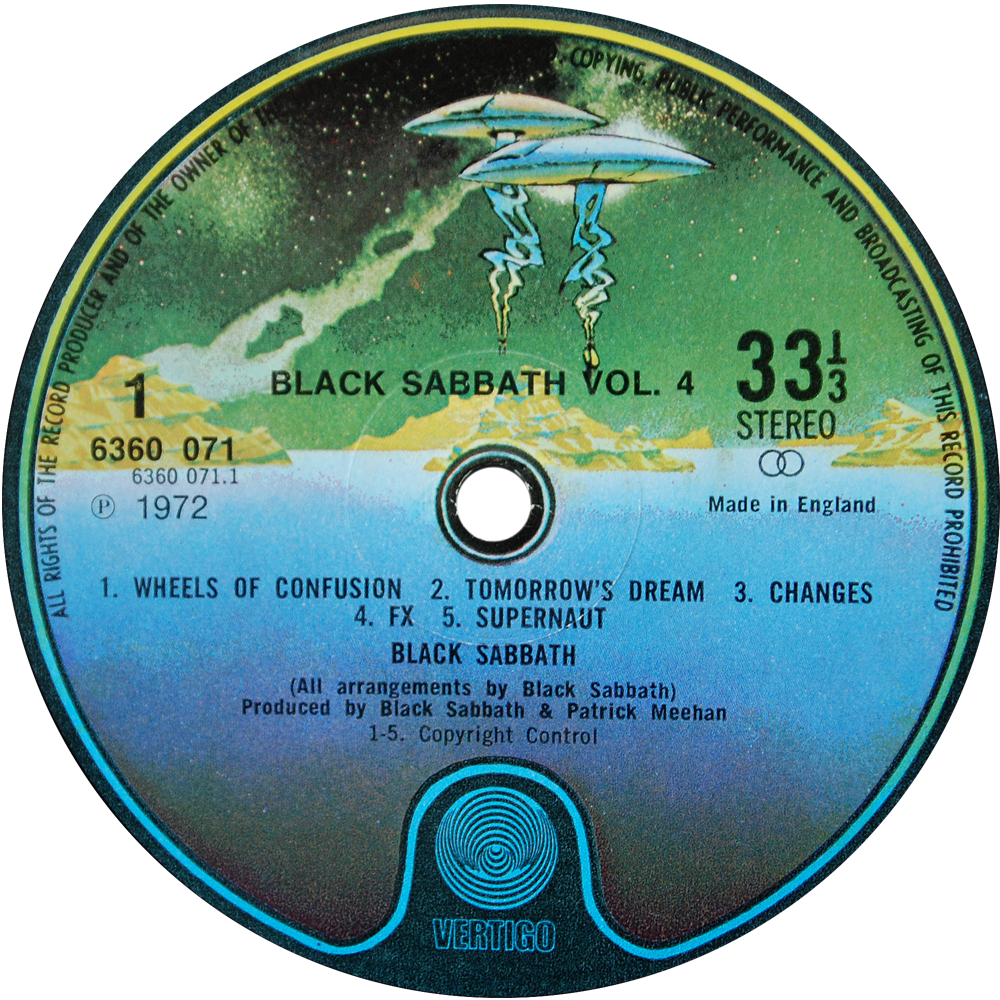

Let’s look at one theoretical example of someone who considers himself or herself a record collector today. They’re a boomer, coming of age in the late ‘60s. They followed all the explosive music developments of the era, from the Beatles to the Rolling Stones, and then to the Doors and Pink Floyd. They went on to “heavier” stuff like Black Sabbath and King Crimson. When the music changed, they followed one of several paths, choosing the more thoughtful music of singer-songwriters like Neil Young, Paul Simon, and Joni Mitchell. By then they were out of college, starting their career, maybe marriage and a family. They didn’t pursue music with as much direction and passion as they had other concerns. They still liked the music they had, and they tried to keep up with newer albums by “their” artists, who kept producing into the ‘70s and ‘80s and even up to today.

So, let’s look at their record collection. They have about 500 LP records. They’ve kept everything they bought in their youth, so there are those Beatles and Stones records. But where are those records? He (for it is a he) has them in boxes in the garage; he hasn’t had a turntable for over 20 years, and even playing his CDs is rare since the player is in his car and he mostly listens to NPR.

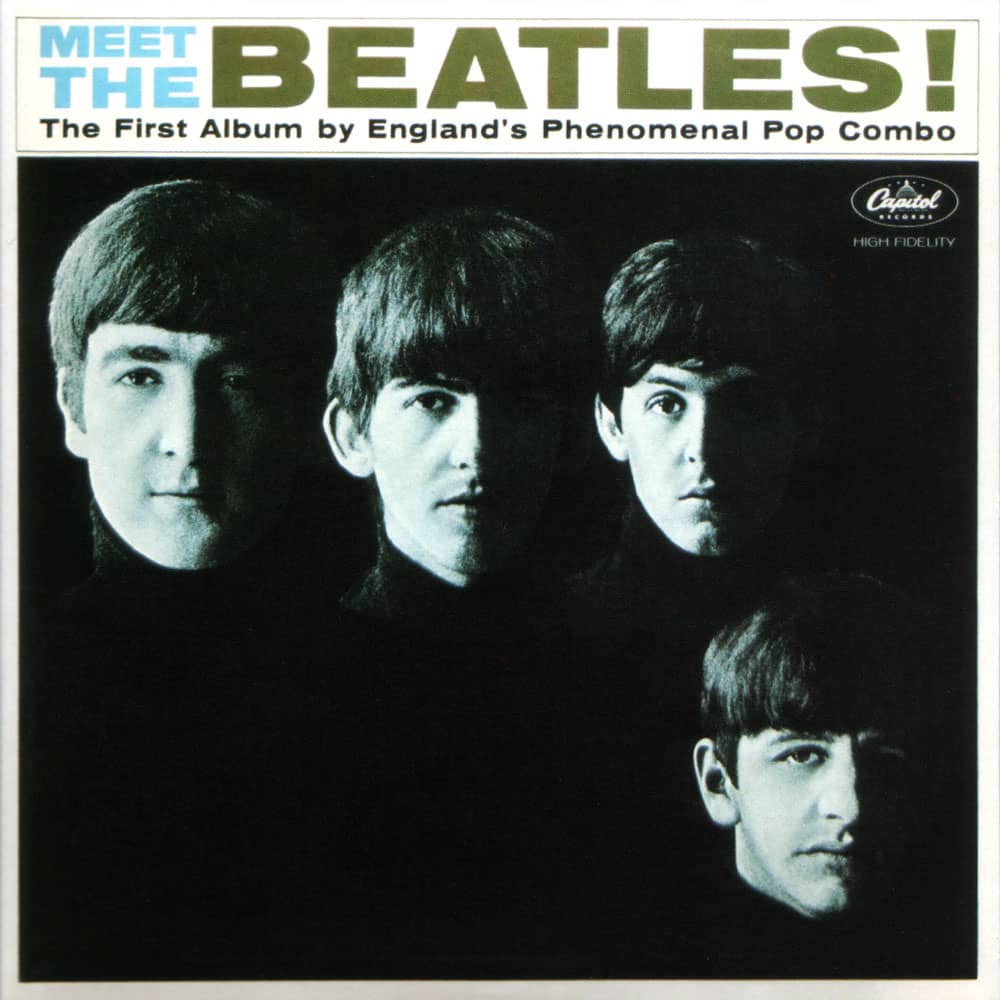

He wants to sell those records. They’re “old.” They’re major artists. They’re “valuable.” He pulls them out of the garage, out of the box, and we can finally get a close look at those records. He has “Meet The Beatles.” He has “Rubber Soul” and “Revolver,” and a copy of “Sgt. Pepper” that folds open to reveal some suspicious remains of plant matter in the middle. He has the “white album” and “Abby Road.” OK, some great albums, classics. Albums that everyone else bought, too, back when they were new all the way up to today as they’ve remained in print in one format or another for many years.

Let’s look a bit closer. Take that copy of “Meet The Beatles.” Hmmm. Looks like he enjoyed playing it a lot. The corners of the cover are a bit bent. There is some rubbing wear on the front and back, probably from all the years of storage. And there’s his name written in black marker. What about the record inside? It still seems to be in its paper sleeve, though that’s quite tattered and ripped. The disc, well, he did love playing that record. Perhaps too well. The record could always be identified as his because his fingerprints are all over it. There are scratches, too, and some kind of marks you can’t tell what they are.

So, this record’s condition is a real negative factor here. He didn’t so much collect this record as use it. Nothing wrong with that, records were meant to be played. Finding an original record from 1964 in really excellent condition is either a happy accident of fate – or a determined act of preservation and collecting. This record gives us a clue as to what kind of collection he has.

So let’s look even closer. This copy of “Meet The Beatles” is on Capitol Records, with a catalog number of T-2047, denoting the monaural version. The label on the disc is the “rainbow” design. So far so good; this in an original first pressing, right? If this was the late 20th Century, the most likely answer was “yes.” But now that’s not good enough.

Take another look at that front cover. “The Beatles” is printed in olive green. On the back cover, you can’t find a producer credit for George Martin. If you look on the label, you can notice songs with both BMI and ASCAP credits. These details are important. They define the specific pressing edition of this LP. Which, it turns out is a third pressing from mid-1964 of the West Coast edition.

In fact there are at least four distinct pressings of this album from the 1960s, with at least 17 variations (Thank you, Bruce Spizer).

Now, Beatles collectors are in a category all by themselves. Their level of attention to detail verges on obsession. But they’re the ones defining the collectability and hence value of these records. Their details and knowledge drive the market.

What about all those other records in this guy’s closet? Well, look at those Rolling Stones records. His albums on the London label like “England’s Newest Hitmakers” and “Now!” are in stereo. But they’re really “stereo,” a fake reprocessed stereo. The preferred versions are the monaural copies, which are now much rarer than the stereo-ized versions.

OK, OK, so the point is made that versions are important. This guy simply bought the records whenever and wherever he found them, just wanting the music, and not thinking about these other factors. Fine, most people bought records that way. The music was the important thing, after all.

Rather than dwell on the details of specific records, let’s look at what the records are that he has. There are those six Beatles albums. But there are only six. There’s no “Introducing The Beatles” on Vee-Jay. No “Something New” or “Beatles ’65,” or either of the soundtracks, or any of many other Beatles albums. So is this a collection of Beatles albums or just a random assortment? There doesn’t appear to be any directed effort to put together a specific group of albums by the band. Perhaps he didn’t care for the music on the other records. Maybe he didn’t have enough money to buy everything. There may be other reasons. But this is certainly not a major Beatles collection.

Similarly, there’s a copy of “In The Court Of The Crimson King” by King Crimson (Atlantic Records, 75 Rockefeller Plaza address), and their “Lizards” album, then “Starless and Bible Black,” and “Discipline” and “Beat.” An erratic, very partial discography. With Neil Young, there’s “Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere,” the ubiquitous “Harvest,” “On The Beach,” “Tonight’s The Night,” “Long May You Run,” then a long gap before “Old Ways,” and nothing newer (except a couple of CDs). Interestingly, the more recent LPs are in better condition, perhaps even untouched or played only once or twice. This sort of pattern runs through almost all the artists in his records. One can easily tell when his interest level fell off.

Wait a minute. What’s that? In the box is something that seems to come from someone else’s collection. It’s an album called “Sea Shanties” by High Tide on the Liberty label. “Oh that,” he smirks. “That’s just some junk I got by accident. They’re nobody. Lotta noise if you ask me.” Well, someone’s junk is another person’s treasure. That High Tide album may be a hundred dollar-album or even more. This just goes to show that even a normal or mediocre box of records may have some “accidental” jewels. You can’t take anything for granted.

The Massive Accumulator

Now let’s look at someone at the opposite end of the spectrum. This guy (another male) has thousands of records. He has LPs, 45s, 10-inch discs, 8-track tapes, cassettes, CDs, even some 78s. His house is filled with records, every room has shelves and boxes. The garage is filled. To look at them, they seem reasonably cared for. The LPs are (mostly) all standing up, in shelves. Many are in plastic sleeves. Pull one out at random, and it looks pretty sharp. The disc is nice and shiny, very well cared for. (We’ll be polite and not ask if he ever played it.) So, is this guy a record collector?

Well, what are these records? Oh oh, I see a whole string of Kostelanetz and Mantovani records, the dreaded “easy listening” types. There are Broadway shows here. Lots of pop vocalists like Teresa Brewer, Dean Martin, and Doris Day. One wall is almost entirely classical, and you can read the labels easily, finding Columbia, RCA, Everest, Musical Heritage Society, and DGG by the dozen. Look another way, and you’ve got lots of classic rock. Lots: Foreigner. Led Zeppelin. AC/DC. Slayer. REO Speedwagon. Heart. Bad Company. Kansas. Boston. Then there are all the sound effects records here, and the documentary records, the Soviet choruses, the English folk music, even some in Chinese and is-that-Tagalog? Then you find the Billy Joel section.

You never knew Billy Joel had so many records. They seem to go on and on. But you notice duplicate copies. Lot of copies. In fact, there are really only about five different Billy Joel albums here, and the rest are copies. Looking around, you see the same kind of story. Many copies of the same record, all over the place. So, does this mean he is serious about collecting? Let’s look at those 23 copies of “The Stranger.” Even if these are original first pressings, they’re not particularly valuable, but they’d still be notable to the collection. However, they’re all early ‘80s pressings (the album came out in 1977), and they all have the same price sticker. Apparently they were all purchased at the same time in the same place at the same discount. And just put on the shelf.

So, is this a collection? Strictly speaking, yes, because of sheer volume and variety. But it appears driven simply for accumulation sake, without a consciousness about why something is being added other than it exists. That’s what this is: An accumulation. It doesn’t take more effort than the physical act of buying. And housing it.

Becoming A Record Collector

The point of all this is to show that in just having a lot of records, no matter what they may be, or how old they may be, is not a “collection” and doesn’t make the owner a “record collector.” Let’s go over some of the factors that go into making the modern record collector:

- Your music collection is a reflection of a personal search. The love of music drives one to discover what can be discovered. If one loves rock, or classical, or reggae, or whatever, the passion is there to find everything that can be found to fuel the passion. If you’re into psychedelic rock, you won’t be satisfied by just having a few Jefferson Airplane or Pink Floyd albums. You’ll dive into the genre to find related groups, and maybe even singles by bands that never had albums. Then perhaps on to other countries, finding the differences between what “psychedelic” meant in the U.S. compared to England, for example.

- Your collection builds way beyond the hits and “famous names.” What makes a hit is often accidental and ephemeral. For any one hit song in a genre, there are dozens if not hundreds of other songs that didn’t make the charts, and they’re just as good – if not better! – than the well-known song. This takes an ability to enjoy music purely as music, not as nostalgia, not as part of your own personal history, but to accept music on its own terms for what it is. If you can do that, you’ll find hundreds of artists and thousands of songs you can love despite not having grown up with them.

- You have a thirst for “originalism.” You look for the first edition of whatever you seek. The first pressing is as close to the source as you can come, it’s the original way the artist and the record company presented the music to the public. It’s like the first edition of a book, or an oil painting instead of a print. You care that your “Meet The Beatles” mentions George Martin on the back cover, and that there are no BMI or ASCAP credits on the label. It’s important that your Vertigo progressive rock album has the b&w swirl label, not the spaceship design. The Fritz Reiner on RCA had better be a “shaded dog.”

- Once you love an artist’s music, you can’t stop. You have to find everything that artist or band released, from their earliest music before they were famous, to long after everyone forgot about them. You don’t forget. You build your collection based on their discography, because. Possession is a passion.

- You care about preservation. You try to obtain the best condition copies you can find or afford. You use proper storage, putting vinyl in audiophile sleeves, album covers in audiophile jackets. You organize the collection in some way that makes sense, not just to you, but also to others.

- You care about the future. Somewhere inside you is an understanding that what you are building is a collection that doesn’t just say something about you, or about the artists or bands in it. You are building a legacy. You are building a representation of an era, or a theme, or a genre, with a deeper understanding.

These are the six most important aspects of being a true record collector – collector of anything, really. Whatever you collect, you show respect for the material you put together, and for yourself. This is not really a system, it’s a consciousness. The rewards may not always be about valuation, but they will always be about satisfaction.